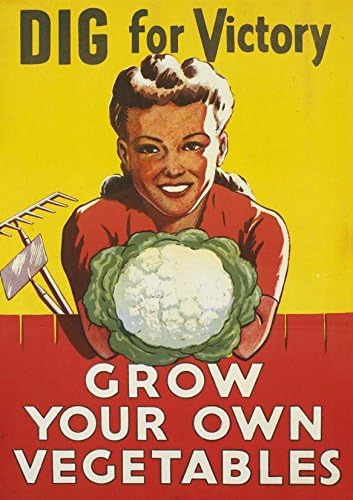

Many parents enjoy spending time with the children at the allotment, teaching them all about the growing process, an incredible journey that starts with a single seed. Others go to the allotment for some peace, regarding their allotment as an idyllic retreat to while away the hours in quiet solitude.

Growing fruit and vegetables helps children to understand more about the food that they eat, for example, that the origins of the humble chip actually go back a lot further than the supermarket freezer department. Experimenting with different crops encourages children to try new things, widening their palate and making them more likely to hit their five-a-day, potentially instilling lifelong healthy eating habits. Feeding children healthy, nutritious food is a priority for most parents and an allotment can ensure a year-round supply of extra fresh fruit and vegetables, but is one plot really enough?

According to Research by John Jeavons and the Ecology Action Organisation, 370 square metres of growing space is enough to sustain one individual consuming a vegetarian diet for one year. With the average UK allotment spanning 250 square metres, in terms of feeding a family of four, one plot would fall woefully short in terms of providing sufficient potatoes or grain. Nevertheless, even the smallest area can be utilised to provide cost-effective, high-yield crops, with gluts frozen or preserved to see the family through the colder months, e.g. apples, rhubarb, raspberries, strawberries, peas and beans. In fact, legumes in particular offer an increased ROI for those with a small plot, providing impressive crops that grow vertically, maximising space efficiency.

In an article published by The Guardian, Jerry Coleby-Williams suggests that 400 square metres is adequate to feed a family of four year-round in subtropical Australia, where he lives. Having been taught by his grandparents, the English-Australian conservationist and gardener explains that the key to success is good soil, adding that it took five years for him to achieve this himself, but that with a 300 square meter garden, his three-person household produces more than enough food for themselves. Indeed, Mr Coleby-Williams reveals that by making marmalade the family have created a lucrative revenue stream, generating enough money to pay the mortgage for approximately six weeks.

One great thing about having an allotment is potential for cross-pollination, with fellow plot holders growing similar crops on site. Some trees, such as apple trees, pear and cherry trees, require another in the vicinity to produce a decent yield. The sharing of labour, knowledge and surplus crops can also be significant pluses. Indeed, if self-sufficiency is the goal, then establishing a cooperative of likeminded growers can go a long way towards achieving this, with gardeners sharing their gluts to support one another.

Where the goal is simply to supplement the family food supply, size isn’t everything. Even in a relatively small space, gardeners can supplement their family’s weekly shop with fresh fruit and vegetables year-round, growing produce with a flavour infinitely better than that found in the shops for just a fraction of the price. Growers also benefit from knowing exactly where their food has come from and how far it has travelled from field to plate.

There are few things as magical as springtime in the UK, daffodils and magnolia blossom reminding us that summertime won’t be far behind. With UK families feeling the pinch, many are rolling up their sleeves and having a go at growing their own. During a parliamentary debate on food security and supply chains at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, Baroness Walmsley addressed a virtual House of Lords, insisting that the best way to ensure food security was for families to grow their own.

In reality, farming is highly skilled work that demands a significant investment of time, undertaking what is, at times, backbreaking work. To feed a family of four would be the equivalent of a full-time job, out in all weathers, with no guarantee of a decent crop at the end of the growing season. If it is too windy, too dry, too wet, too hot or too cold, crops will fail. A two-week holiday in Mallorca could trigger a drought from which many crops would struggle to recover. Becoming completely self-sufficient would require an inordinate commitment of time that is simply beyond most modern families. Neglect the plot for a week and menaces like couch grass and bind weed will set in, spreading from exposed areas to suffocate crops.

Then there are pests. Slugs, snails, mice, voles, rats, squirrels, birds, badgers, foxes, moles, caterpillars, wasps, ants, aphids, pear midge, coddling moths and carrot fly. The allotmenteer will wage war with them all in a seemingly never-ending battle. Baskets of produce will also need to be soaked and scrubbed to remove every last trace of this veritable smorgasbord of biodiversity.

However, having your own allotment presents a multitude of upsides too, enabling families to grow pretty much whatever they want, subject to the site rules. Alongside good old British stables like runner beans and rhubarb, many allotmenteers are becoming increasingly adventurous, growing produce that requires a hotter climate in line with the warmer and drier summers we are beginning to experience. Some allotments allow animals such as chickens and even sheep and goats to be raised on plots.

From an environmental perspective, allotments have an extremely positive impact, driving down growers’ carbon footprints by eliminating the need for packaging and the transportation of produce. Growing organically offers even greater environmental benefits, reducing levels of harmful chemicals in the soil and meaning that the produce picked has even greater health benefits.

One of the biggest incentives of taking on an allotment is the prospect of saving money on grocery bills. However, keeping a plot in good order can be a costly process, particularly at the beginning. On top of annual rent, which can be anywhere between £10 and £150 upwards per annum, allotmenteers must invest in tools, seeds, plants, and essentials like string, gardening gloves and bamboo canes. They will also need to think about landscaping, particularly if the plot they are taking on has been neglected, creating paths, etc.

These costs can add up to significant sums, although it is important to remember that most of these items will only need to be purchased once. Although the cost of setting up their allotment just how they want it could run into hundreds of pounds, this will be a one-time expenditure for many growers, enabling them to enjoy years of growing at minimal future cost.